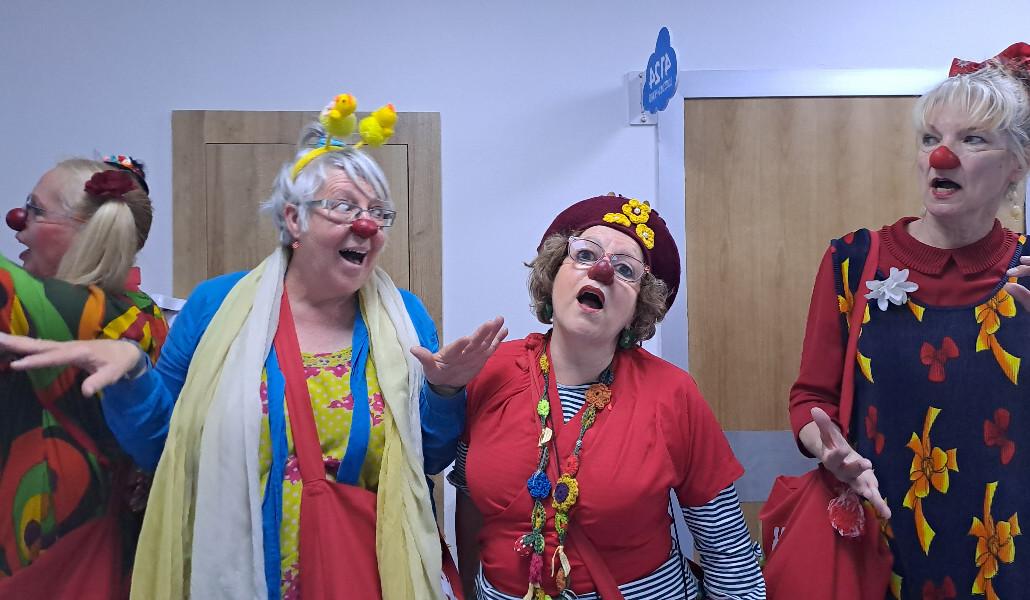

Hospital Clowns on a Special Mission: "The Clown's Playmate is Not the Illness, but the Person and Their Emotions" (video)

Support A1+!When people in colorful costumes boarded the plane from Amsterdam to Tbilisi, the passengers could not remain indifferent. They had drawn everyone's attention even at the airport when they started singing.

"Hello, I'm Jack Chrous or the clown Jaco," says the 61-year-old man, who is the only male among the 13 clowns traveling to Georgia. "I love traveling with these women," he jokes, who is an elementary school teacher by profession. He also works with children as a clown, but the methods are different; now he plays more with them. "I'm very happy, interacting and playing with little children are beautiful moments."

Jako and the others do not work in a circus. They are hospital (clinic) clowns who, after receiving certain training and preparation, visit healthcare facilities with the aim of boosting patients' moods and conveying hope and positive emotions.

Patti Ickx is from Belgium. On workdays she is a physiotherapist, and after work and on weekends she is the clown Frizole.

"I think being a clown is a way of communicating with people without knowing a foreign language," she says. "You open your heart and an energetic miracle happens."

"In the circus, a clown performs a stage act. We hospital clowns don't perform a show. We simply improvise what we feel at that moment," Patti Ickx explains.

Isn't it psychologically difficult to work with patients with various, sometimes terminal, illnesses? "It's not essential for us what illness they have. We don't think about that. Our playmate is the person, regardless of age or illness; we do everything for them to become our playmate and be happy," she says.

Patti Ickx has her own prescription for happiness: "Stay open, be curious, allow yourself to be surprised, and be generous with your love."

"The clown doesn't see the illness, but only the person, the emotions, and works with those emotions," says Laurence Quetel, or the clown Oh-la-la. Unlike the others, she is a professional clown. "I'm very curious, my clown is just like that," she says.

Laurence Quetel is French but lives in the Netherlands. Performing as a clown was initially a hobby, then she received relevant training and now teaches others the subtle art of being a hospital clown.

We end our conversation with her when the minibus arrives at one of Tbilisi's hospitals. But the clowns don't immediately enter the building. For about 15 minutes, they do a psychological "exercise" led by Laurence Quetel.

"Our group of volunteers is not only made up of the elderly, it's just that no young people joined this trip," says Anee Cosse, president of the Dutch organization Out of Area. The hospital clowns came to Tbilisi through the joint efforts of her organization and the Georgian youth organization Droni. Anee Cosse and her retired military husband founded the Out of Area foundation, particularly to support children affected by war in the Balkans. Subsequently, the mission's scope expanded, and today it helps not only children. Incidentally, the hands in the organization's logo symbolize the four children they first helped.

"The four hands symbolize that together we can do a lot. But they are the hands of four little ones we helped years ago in Bosnia. For example, one is the hand of the little girl Sabina. She was only 3 years old, living with her mother in a refugee camp under terrible conditions. Now she lives in Germany, has graduated from university, is married," Anee Cosse recounts. We ask if she is also a hospital clown. "I tried, but that wasn't my way of communicating and helping people," she smiles.

Karine Asatryan