Mistrust, chaos and panic: how disinformation affects people and what can be done about it (video)

Support A1+!“Americans can create biological weapons”, “Georgia deliberately infects mosquitoes and sends them to Russia”, “Data on mass deaths in Georgian laboratory published”.

These are not lines from an apocalyptic Hollywood thriller, but examples of Russian media reports about the Richard Lugar Center for Public Health Research, located on the outskirts of Tbilisi. The laboratory is a partnership project between Georgia and the United States. But the centre’s activities for some reason worry Russia, which is spreading disinformation and propaganda about the laboratory.

“In September 2018, the whole world was talking about Russia’s use of the Novichok nerve agent in the UK. At the same time, Russia began to talk about the Lugar laboratory as a place where the United States allegedly produced biological weapons for use against the Russian Federation,” says Sopo Gelava, a researcher at the Georgian Media Development Fund.

If you type “Lugar Lab” into Google or YouTube search engines, you will see that most of the frightening news about it is produced by Russian media. To counter these myths, the Lugar laboratory opened its doors and showed what was going on inside.

“More Russian journalists visited the laboratory than Georgian ones,” says Paata Imnadze, Scientific Director at the National Centre for Disease Control and Public Health of Georgia.

But even regular tours of the laboratory did little to change the Russian media narrative. For example, the Russian news agency Sputnik described the “open day” at the laboratory in a dismissive and suspicious way.

Of course, not a single one of the “sensational” statements by Russian media about the Lugar laboratory was true. All of them were disproved by health experts. But these statements achieved the desired effect – 20% of Georgians believe that the laboratory contributes to the spread of epidemics. This is how disinformation works in the post-truth era.

Disinformation = mistrust, chaos, panic

In 2017, the European Union launched the EUvsDisinfo.eu online portal to counter disinformation from Russia. It is published in three languages - English, Russian and German. The site has a disinformation database, which so far contains nearly 8,000 examples of disinformation starting from 2015.

Half of the disinformation messages were directed against six countries – all former Soviet republics – Azerbaijan (31), Armenia (80), Moldova (132), Belarus (252), Georgia (345), and Ukraine (3,193), which Russia wanted to keep in its sphere of influence.

Many of the examples of disinformation used against these countries are aimed at causing panic, undermining the domestic political situation, intimidating, or increasing military tension (in the case of Ukraine). Often the messages look simply absurd, often they are naked lies or they twist information. But their poor quality doesn’t make them less effective.

“Ukraine faced the highest level of disinformation during the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the invasion of Donbass. These were hybrid propaganda tools in the media and social networks,” says Kristina Zelenyuk, political commentator for the Ukrainian portal Segodnya.

According to the Armenian media expert Samvel Martirosyan, the disinformation market is vast. It employs professionals who are constantly looking for new tools and methods of manipulating people.

“Now you can sow panic in a few hours using social media. Information spreads so fast that it’s almost impossible for people to identify disinformation,” says Samvel.

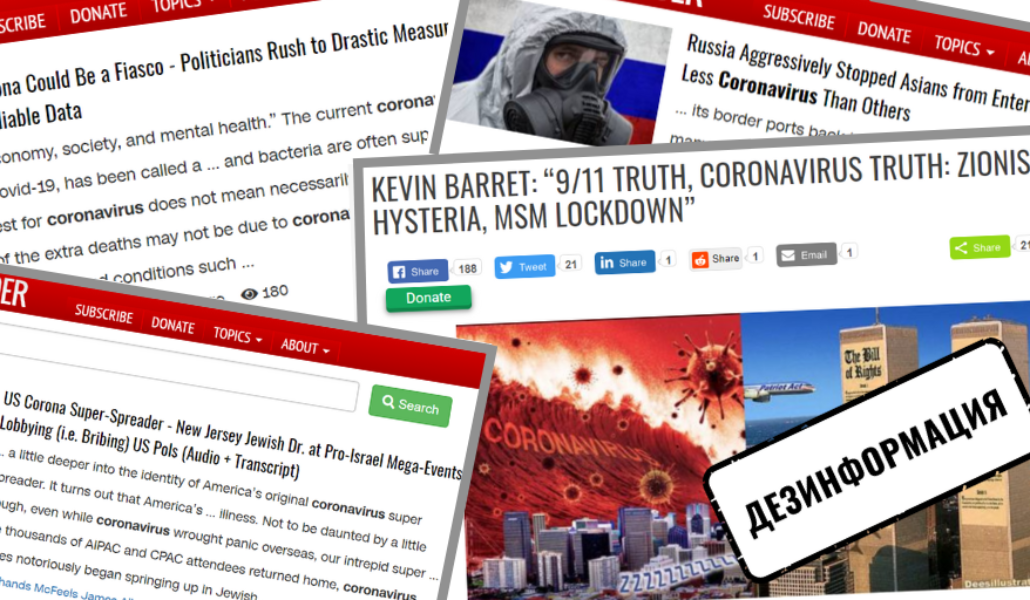

In March 2020, the European External Action Service published a special report, “COVID-19 Disinformation” with a special chapter dedicated to “pro-Kremlin disinformation”.

In February-March 2020 alone, the EUvsDisinfo database registered over 110 examples of coronavirus disinformation distributed by pro-Russian media. These examples were in line with the Kremlin’s traditional strategy of sowing mistrust and chaos, aggravating crisis situations and public concern. Moreover, misinformation directed at the Russian audience described the virus as a form of foreign aggression. It claimed that coronavirus originated from secret American or Western laboratories. Disinformation for domestic audiences focused on conspiracy theories about “global elites” which deliberately use the virus as a tool to achieve their goals.

Many fake and manipulative news based on shocking conspiracy theories gradually change the perception of information. At first, people simply don’t react to disinformation, then they react to it but don’t believe it, and then, due to the frequency and volume of such materials, they start to believe fake or misleading narratives. This is the goal that organisations and countries that manipulate information are trying to achieve.

“Disinformation is a terrible threat. It concerns not only those who are poorly educated or not well versed in politics. In fact, everybody is under attack,” says Alexander Starikevich, editor-in-chief of the Belarusian ‘Solidarity’ internet portal.

Critical thought ambassadors against fake news

The news agenda in our digital world changes so fast that people simply do not have time for deep analysis of events. That’s why fakes and manipulation are often perceived as real news. Different media, organisations dedicated to exposing fakes, as well as volunteers, are all working on deconstructing fake narratives.

“But this work should not be limited to a small group of people. The whole of society should benefit from it. We must educate it,” says Samvel Martirosyan.

Young people are effective helpers in the fight against disinformation. This is the opinion of Anina Tepnadze, director of the Georgian online media platform On.ge.

In her view, young people know more about disinformation and they are more sceptical. Therefore, they can teach their parents and neighbours how to consume information properly.

“But to engage young people, they should receive a clear message that it is really important, that this is not only ‘their problem’, but an issue for everyone. Then young people can be good ambassadors of truth,” says Tepnadze.

In the view of Alexander Starikevich, to prevent people from believing disinformation, we need to start teaching critical thinking from nursery-school age.

He points out that it is difficult to work with people who have already formed their worldview. “Their reaction is frequently ‘Why are you lecturing me? I understand everything myself.’ But there will always be a part of the audience that is open to explaining, and you need to work with them,” says Starikevich.

There are, however, more radical methods of fighting disinformation – for example, using legislation. Saadat Mammadova, head of the news department of the Azerbaijani CBC television channel, believes that it is necessary to adopt international legislation or a charter to solve the problem of fake news.

“Fake News is turning into a national security issue, a tool that can destabilise the world, and it's time to consider it in the security context,” stresses Mammadova.

Bloggers against disinformation

The growing popularity of social networks has led to the emergence of bloggers as competitors to the traditional media. These bloggers gather large audiences. Bloggers can be good helpers in countering disinformation.

Samvel Martirosyan believes that “people often trust bloggers more than traditional sources of information. Given this degree of trust, opinion leaders can jointly stop waves of disinformation and rumours.”

The popular vlogger from Moldova, Dorin Galben, believes that social networks have become a “nest” of fake news that needs to be unmasked. “Our role [as bloggers] is to reach out to as many people as possible, inform them about the phenomenon of fake news and the impact that ‘fake news’ can have on the future of the country and its citizens,” he adds.

Azerbaijani blogger Seymur Kazimov also speaks about the responsibility of opinion leaders. He believes bloggers should deconstruct fakes and disinformation, and counter them publicly.

“Bloggers need to publicly highlight examples of fake publications of friends or acquaintances, or people they follow. Specific examples always work better than theory,” says Anton Motolko, who is a blogger and civic activist from Belarus. “The first and most important thing is not to become a source of fake distribution ourselves. There is a golden rule here: if you suspect it is a fake, don’t publish it,” he adds.

Georgian TV presenter and blogger Zura Balanchivadze advises to look carefully at the headlines. This frequently helps determine if a particular piece is a lie. “Fake news often has sensationalist headlines or features strong exaggeration. Also, analyse those sites where you see dubious information – ask what type of content these resources usually publish,” adds the blogger.

“Blatant lies are easy to spot. But half-truths or manipulation of facts are harder to discern. Consult with experts in different fields. Learn to distinguish facts from subjective opinions. Do not take everything at face value. Always doubt, think and ask questions,” advises Roman Vintoniv, TV presenter and vlogger from Ukraine.

Author: Viktor Kischak